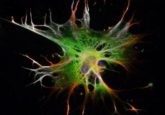

How do our brains respond to social interaction?

Four studies describe the alarming ways in which our brains respond to social interaction.

Findings presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (San Diego, CA, USA; 12–16 November 2022) are shedding light on the means by which the brain processes social exchange. Responses to interpersonal interaction are dictated by myriad nuanced drivers and can have long-term consequences on brain function. These complexities are only complicated further by the march of technological progress and parallel changes in socio–cultural approaches to social interaction. However, as advances in technology drive changes in social conduct, advances in technology are also facilitating new ways to measure and quantify human behavior and neurological alterations with ever-greater accuracy.

Frequencies of highs and lows

A study from the University of Geneva (Switzerland) outlined the reward circuit in the brain responsible for differentiating between positive and negative interactions. While these reward circuits can assess how enjoyable an interaction may have been, researchers lack an understanding of how individual circuits encode the qualitative associations that influence future behaviors.

Tests revealed that rodent brains display activity between the insular cortex and the nucleus accumbens, finding that the connecting circuit responded with low frequency activity to positive experiences and high frequency activity to negative ones. These frequencies may lay the guidelines for future interactions. [1]

Survivalist cells

Researchers at Harvard University (MA, USA) investigated the neurological underpinning of the survival instinct behind social interaction-seeking behavior. They found novel groups of hypothalamic neurons that respond to social circumstance. These cells may provide an entry point for examining the neural circuitry encoding the psychological dynamics of social interaction and social isolation. [2]

How did anxiety develop during human evolution?

How did anxiety develop during human evolution?

A study has demonstrated how neurotransmitter transporter genotypes affect brain function, particularly the anxiety brain mechanism.

Double up or quit

If you are lacking a sense of cynical bemusement in your day, try this study from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (NY, USA): researchers found links between traumatic social experiences and future social reward impairment. It is already established that socially avoidant behaviors and psychiatric damage can follow traumatic social experiences, but to examine this further, researchers exposed mice to social failure-related stress. They found that stress/threat-response neurons encoded the trauma in the lateral septum – a reward-related area of the brain. The researchers observed that, in one of nature’s most self-defeating all-or-nothing gambits, hyperactivation of these neurons in non-threatening scenarios caused the mice to avoid social interaction in the future, regardless of the previously experienced rewards. [3]

Comfortably numb

Finally, a study that may provoke your inner nihilist, by researchers at Skidmore College (NY, USA). They examined the reasons behind altruistic behavior in social animals. Researchers describe “emotional contagion” – the ability to experience another’s pain – which is theorized to drive those afflicted by it towards altruistic actions in order to alleviate their own discomfort. Research also suggests that some people understand this staggering viral psychological phenomenon to be ‘empathy’.

‘Free’ rats had the ability to help a trapped cage mate by opening the trap with an external unlocking mechanism. However, half of the trapped mice were given midazolam, an anxiety-reducing drug, to reduce their distress. The researchers observed that the ‘free’ rats were less likely to open the apparatus if the ‘trapped’ rats did not signal significant distress. [4]

You could make an economy out of this. No, don’t.