Studying honey bee brains in vivo

Researchers integrate a fluorescent calcium sensor into honey bee brains to study their neural activity in response to odors.

Insects are an important model species and share more than 60% of their DNA with humans, despite more than 600 million years of independent evolution. Honey bees are a common model organism with complex social behavior, simultaneously performing sophisticated behaviors and orientation, communication, learning and memory abilities. They also display the most advanced level of sociality found in eusocial insect societies, insects that live in colonies and divide labor between themselves.

Honey bees’ sophisticated behavior makes them an interesting model organism to study brain function and neural processing; however, until now we lacked the tools to study this on a neural basis. Researchers across universities in Germany, France and Italy have developed a fluorescent calcium sensor that enables direct observation of honey bee brains.

The holy grail of neuroimaging: the revolutionary new sensor

The holy grail of neuroimaging: the revolutionary new sensor

The development of a novel sensor allows electrical brain activity to be measured for a longer period of time and deeper within the brain than previously possible.

To integrate the sensor into the bees’ neurons, the researchers first inoculated a specific gene sequence into over 4,000 bee eggs. This was followed by a lengthy breeding, testing and selection process. This resulted in a total of seven queen bees carrying the genetic sensor, which, when reproducing in their colonies, was transmitted to some of their offspring.

Calcium is important to many functions of the nervous system, including nerve cell activity. The modified genetic code made brain cells produce a fluorescent protein when calcium signaling occurred, enabling the researchers to monitor the areas that are activated in response to environmental stimuli.

“The realization of this ‘sensor bee’ was particularly challenging because we had to work with the DNA of queen bees,” explained senior author Martin Beye (Heinrich Heine University; Düsseldorf, Germany). “Unlike fruit flies, the queen bee cannot easily be maintained in the laboratory, because each one needs its own colony.”

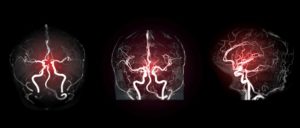

The resulting sensor was used to study the bees’ sense of smell and how the perception of smell is encoded in neurons. The researchers observed their behavior and response to different odors using a high-resolution microscope. They detected which brain cells are activated by smells and how the information is distributed in the brain in vivo.

Bernd Grünewald (Goethe University; Frankfurt, Germany), co-author of the study, concluded, “The new ‘sensor bee’ makes it possible to study how communication works within colonies and, more generally, how sociality affects the animals’ brains.”