The path to lysosome repair is the PITT pathway

Refer a colleague

For the first time, the pathway through which cells repair damaged lysosomes has been observed and described.

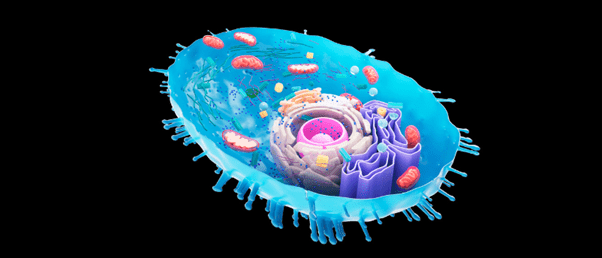

Lysosomes are the recycling center of a cell, where molecular waste is degraded into the building blocks needed to create new organelles. They contain digestive enzymes to break down molecules and are surrounded by a membrane to prevent the acidic contents from harming other parts of the cell. However, lysosome damage is associated with aging and a range of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders.

In healthy cells, any damage to the protective membrane is quickly repaired. So, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh (PA, USA) studied this repair process, hoping to understand more about diseases associated with leaky lysosomes and improve the treatment options available for them.

First author Jay Xiaojun Tan and the team began by damaging lysosomes in lab-grown cells and measuring the proteins that arrived to repair the membrane using immunoblotting. Within minutes, an enzyme called PI4K2A had accumulated and was generating notable amounts of the PtdIns4P signaling molecule.

Tan explained, “PtdIns4P is like a red flag. It tells the cell, ‘Hey, we have a problem here.’ This alert system then recruits another group of proteins called ORPs.”

The ORPs (oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP)-related protein) connect the PtdIns4P signaling molecule on the lysosome to the endoplasmic reticulum, which is the cellular structure involved in protein and lipid synthesis. Then “the endoplasmic reticulum wraps around the lysosome like a blanket,” explained Toren Finkel, the senior author of the study. “Normally, the endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes barely touch each other, but once the lysosome was damaged, we found that they were embracing.”

This arrangement facilitates the transport of cholesterol and a lipid called phosphatidylserine to the lysosome, which are needed to fix and reseal the lysosomal membrane to prevent the digestive enzymes from doing any more damage to the cell.

Artificial fertilization reveals key protein in sperm–egg fusion

Artificial fertilization reveals key protein in sperm–egg fusion

An international team of researchers has discovered a fundamental protein in human fertilization, called MAIA, which could lead to an improved understanding of infertility.

The final step of the membrane repair operation occurs when phosphatidylserine activates a protein called ATG2, which acts like a bridge transporting other lipids to the lysosome to seal any remaining tears.

“Our study identifies a series of steps that we believe is a universal mechanism for lysosomal repair,” said first author Jay Xiaojun Tan. The researchers named the mechanism phosphoinositide-initiated membrane tethering and lipid transport or, for short, the PITT pathway in honor of the University of Pittsburgh.

It is likely that small breaks in the lysosome membrane of healthy people are repaired rapidly by the PITT pathway. However, if there is significant membrane damage or the pathway is no longer functioning, the membrane is not sufficiently fixed, leading to the accumulation of leaky lysosomes.

After identifying the PITT pathway, the researchers looked into its role in Alzheimer’s because a key step in Alzheimer’s progression is the leakage of tau fibrils from damaged lysosomes. Tan deleted the gene for PI4K2A – the enzyme responsible for starting the PITT pathway – using CRISPR and found that the spread of tau fibrils dramatically increased. This suggests that the PITT pathway could play a role in the progression of Alzheimer’s, so the researchers hope to develop mouse models to find out if this lysosome-repairing pathway can be used to prevent the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

“What’s beautiful about this system is that all of the components of the PITT pathway were known to exist, but they weren’t known to interact in the sequence or for the function of lysosome repair,” commented Finkel. “I believe these findings are going to have many implications for normal aging and for age-related diseases.”

Please enter your username and password below, if you are not yet a member of BioTechniques remember you can register for free.