Chipping away at complex inflammatory diseases

Multiomic analysis of a new, multi-tissue, organ-on-a-chip disease model has shed light on complicated inflammatory conditions.

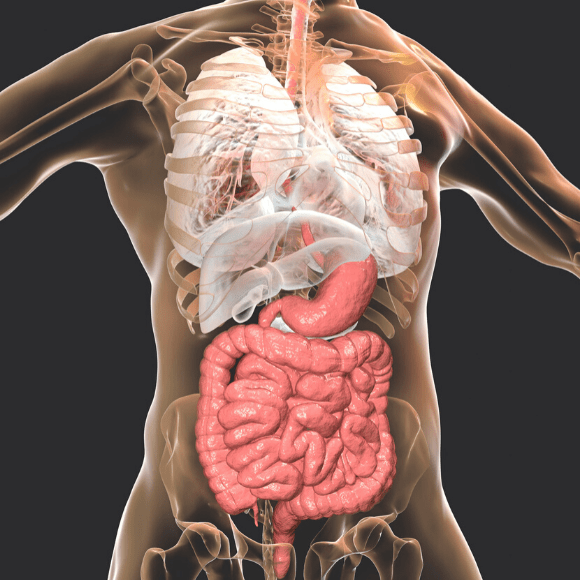

Twenty years on from their original liver chip, bioengineers from the Griffith’s lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MA, USA) have created a multi-tissue physiomimetic model enabling the study of the relationships between organs and the immune system. They hope the ‘physiome-on-a-chip’ will help elucidate the paradoxical roles of circulating immune cells and the microbiome in chronic inflammatory diseases.

Up to 80% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis, an autoimmune liver disease, also suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In an about-turn, IBD increases the risk of autoimmune liver disease.

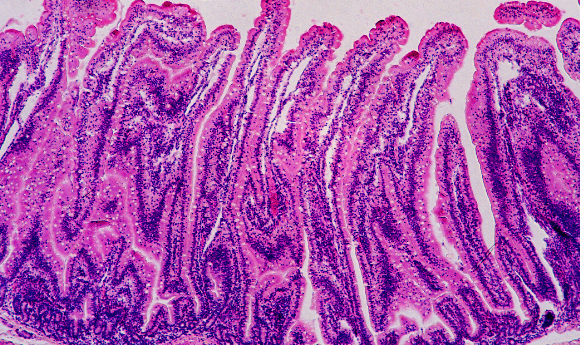

The new system links three microphysiological systems (MPSs) – one modeling ulcerative colitis colon, one a healthy liver and one the immune system, together representing the gut—liver—immune axis. Each MPS comprised all relevant cell types, as well as a specialized microenvironment and perfusion, and could communicate fluidically with the other MPSs.

When connected, tissue physiology was different compared with during isolation, with inflammation in the ulcerative colitis MPS decreased when exposed to the healthy liver MPS. What’s more, the team observed increased activity of genes and cellular pathways related to metabolism and immune function.

A modern-day Frankenstein’s monster?

A modern-day Frankenstein’s monster?

Lab-grown model of the human body comprised of an integrated body-on-a-chip multi-organoid system could pave the way for quicker pharmaceutical testing.

The addition of circulating Th17 and CD4+ T-reg cells increased inflammation, recreating features of IBD and autoimmune liver disease.

In another paradox, short-chain fatty acids – produced by gut bacteria – have been shown to both reduce and increase inflammation in various studies. In the current study, their addition resulted in increased inflammation only if T cells were present.

“The hypothesis we formed, based on these studies, is that the role of short-chain fatty acids seems to depend on how much the adaptive immune system (which includes T cells) is involved,” explained Martin Trapecar, lead author of the study.

The team expects the approach will also be useful to model other complex diseases. “Now we have options to really decrease or increase the level of disease complexity, under controlled and systematic conditions,” Trapecar noted.