How helpful heart hormones stave off obesity

Researchers increased peptide activity in fat tissue to prevent obesity and insulin resistance caused by a high-fat diet. Will these findings help fight metabolic disease in the future?

Improved natriuretic peptide signaling in fat tissue, rather than skeletal muscle, can prevent high-fat-diet induced obesity and insulin resistance.

Credit: Sheila Collins, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute

The heart naturally produces sodium-regulating hormones called natriuretic peptides (NPs) that benefit metabolism by helping to control blood pressure and convert white fat into brown fat. However, scientists investigating the link between obesity and poor circulation of NPs have not fully understood the tissue sites where the peptides most exert their metabolic influence.

Now, in the journal Science Signaling, a team of researchers shows that improved NP signaling in fat tissue, rather than skeletal muscle, can prevent high-fat-diet induced obesity and insulin resistance.

“I think this study certainly shows that targeting natriuretic peptides in fat tissue could be very promising for therapeutic purposes,” said senior author Sheila Collins from Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) in La Jolla, California. “This also shows that when it comes to obesity, NP signaling may be involved in a lot of communication going on between fat tissue, the liver, and other organs that we do not yet understand sufficiently.”

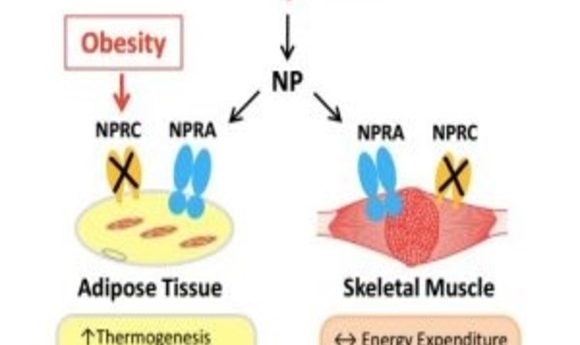

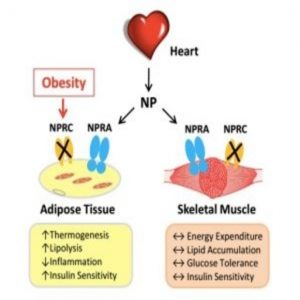

Individuals struggling with obesity and insulin resistance typically have fewer NPs circulating in their blood. Instead, they posess a greater abundance of NP clearance receptors (NPRCs), which may remove the NPs from circulation and degrade intercellular NP signaling overall.

To investigate the link in different tissue sites, Collins’ team made targeted deletions of NPRC receptors, either in adipose tissue or the skeletal muscle of mice fed a high-fat diet. While mice with NPRC deleted from skeletal muscle did not show much metabolic improvement, mice with NPRCs deleted from adipose sites were protected from weight gain, showed greater insulin sensitivity, and displayed completely healthy livers. They also showed enhanced energy production and sugar consumption by brown fat.

“What was also very interesting was that the three major adipose depots that we studied each displayed different metabolic signatures,” said Collins. “We saw improved thermogenesis in brown fat, increased mobilization of fuel in inguinal fat, and in the gonadal fat, there were markers of increased cell number and the ability to take up and store energy in the place that it belongs, as opposed to being stored in the liver where it doesn’t belong.”

“From a clinical point of view, we now have to understand why these different fat depots seem to be responding differently to NPs doing different jobs and how the signaling of these peptides from adipose tissue is being received by the liver and other organs,” explained Collins. “Then we can know what to best target.”