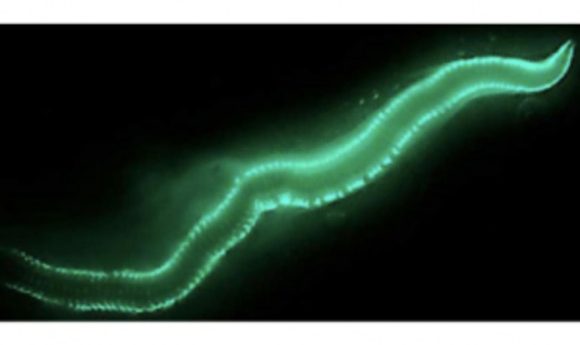

Illuminated: the glow of the Bermuda fireworm

Unique luciferase discovered in bioluminescent Bermuda fireworm.

© James B. Wood, Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences

Researchers from the American Museum of Natural History (NY, USA) have discovered the enzyme responsible for the glow of the Bermuda fireworms during mating season, which has not been seen in any other bioluminescent animal. The enzyme could have potential to tag molecules in biomedical research.

The glow of the Bermuda fireworm was first documented by Christopher Columbus in 1492 but it took until the 1930s for the phenomenon to be explained. The fireworms’ mating ritual is known for its precise and unusual nature. During summer and autumn seasons, at 55 minutes after sunset on the third night after the full moon, spawning female fireworms secrete luminescence in order to attract males.

“The female worms come up from the bottom and swim quickly in tight little circles as they glow, which looks like a field of little cerulean stars across the surface of jet black water,” commented Mark Siddall, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History’s Division of Invertebrate Zoology and the study’s corresponding author.

“Then the males, homing in on the light of the females, come streaking up from the bottom like comets – they luminesce, too. There’s a little explosion of light as both dump their gametes in the water. It is by far the most beautiful biological display I have ever witnessed.”

In order to further understand this phenomenon, the team set about analyzing the transcriptome of a dozen of the female fireworms. In the study, published in PLOS ONE, they detail their discovery of a new kind of luciferase enzyme that was distinct from any found in other bioluminescent animals. The authors are optimistic that this new kind of luciferase could be of use for tagging in biomedical research.

“It’s particularly exciting to find a new luciferase because if you can get things to light up under particular circumstances, that can be really useful for tagging molecules for biomedical research,” concluded Michael Tessler, a postdoctoral fellow in the American Museum of Natural History’s Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics and co-author of the study.