What do burnt toast and dinosaurs have in common?

Refer a colleague

Dinosaur soft tissues can be chemically preserved in a process comparable to that which causes dark staining on burnt toast.

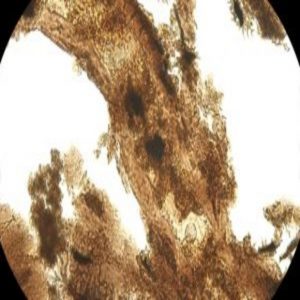

Dinosaur blood vessel with adjacent bone matrix that still contains bone cells. They are morphologically preserved, but chemically altered through oxidative crosslinking. Credit: Jasmina Wiemann.

A team of researchers from a collaboration led by Yale University (CT, USA) has concluded that, as unusual as it may seem, burnt toast and dinosaurs actually have something in common. Both contain chemicals that can transform proteins into new components under the right conditions. The researchers believe this process could be the key to understanding how soft tissue in dinosaur bones have survived for millions of years.

“We took on the challenge of understanding protein fossilization,” explained lead author Jasmina Wiemann (Yale). “We tested 35 samples of fossil bones, eggshells, and teeth to learn whether they preserve proteinaceous soft tissues, find out their chemical composition, and determine under what conditions they were able to survive for millions of years.”

Hard tissues, including bones, eggs and teeth survive fossilization extremely well, whereas soft tissues, including blood vessels, cells and nerves, usually decay rapidly after death, and completely degrade within 4 million years.

However, dinosaur bones behave very differently and have been the subject of much debate between scientists as they are approximately 100 million years old, occasionally with these soft tissues preserved.

No conclusive answers for this had been reached, until now. Wiemann and colleagues noticed that soft tissues are often preserved within oxidative environments, such as sandstones and shallow, marine limestones. They decalcified fossils and imaged the released soft tissue structures using Raman microspectroscopy, which can analyze both organic and inorganic elements without destroying the sample.

They discovered that the soft tissues were transformed into advanced glycoxidation and lipoxidation end products, which don’t degrade and can be compared to the chemicals that cause the dark layer on burnt toast. The end products are hydrophobic, difficult for bacteria to consume and are characterized by a brownish color that stains the hard tissues that contain them.

“Our results show how chemical alteration explains the fossilization of these soft tissues and identifies the types of environment where this process occurs,” commented co-author Derek Briggs (Yale). “The payoff is a way of targeting settings in the field where this preservation is likely to occur, expanding an important source of evidence of the biology and ecology of ancient vertebrates.”

Please enter your username and password below, if you are not yet a member of BioTechniques remember you can register for free.