Disorganized nature of Taq polymerase in DNA replication uncovered

A new study on genetic sequencing finds that DNA replication is not as accurate as was previously thought, which could impact a range of fields, from medicine to the study of evolution.

DNA polymerases are a group of enzymes that are essential to life due to their role in catalyzing DNA replication and repair. One such enzyme is Taq polymerase (Taq), which takes its name from Thermos aquaticus, the microorganism it was first discovered in. Taq is a key enzyme in DNA replication and is regularly used in PCR, including for COVID-19 detection and forensic analysis. Now, researchers from the University of California Irvine (CA, USA) have discovered that this enzyme does not behave as scientists had assumed.

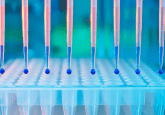

“Instead of carefully selecting each piece to add to the DNA chain, the enzyme grabs dozens of misfits for each piece added successfully,” explained Gregory Weiss, the co-corresponding author of the study. “Like a shopper checking items off a shopping list, the enzyme tests each part against the DNA sequence it’s trying to replicate.” This was observed by monitoring individual Taq molecules using a solid-state electronic technique with microsecond resolution.

There’s something fishy about that pet food…

Researchers used DNA barcoding technology to analyze different pet food products to determine the contents of vague terms such as “ocean fish” or “white fish”.

It is well known that Taq’s ability to reject wrong bases is essential for correct DNA replication; however, this research has found that Taq also rejects correct bases and does so frequently. “It’s the equivalent of a shopper grabbing half a dozen identical cans of tomatoes, putting them in the cart, and testing all of them when only one can is needed,” added Weiss.

Learning that Taq is not entirely accurate could have implications in many fields of research, including how evolutionary histories are interpreted from ancient DNA. Currently, researchers need to make assumptions about how DNA changes over long periods of time, which relies on accurate DNA sequencing.

Accurate genome sequencing is essential in medicine, especially in the development of personalized medicine, as everyone has a unique genome with different mutations at different points in the sequence. Some of these mutations are harmless, whilst others will result in certain diseases. Phillip Collins, who is also the co-corresponding author on this paper and whose lab created nanoscale devices to study Taq’s behavior explained: “How do you guarantee to a patient that you’ve accurately sequenced their DNA when it’s different from the accepted human genome? Does the patient have a rare mutation? Or did the enzyme simply make a mistake?”

This research could lead to improved versions of Taq being developed, making DNA replication more accurate and efficient.

“We’ve entered the century of genomic data,” said Collins. “At the beginning of the century we unraveled the human genome for the very first time, and we’re starting to understand organisms and species and human history with this newfound information from genomics, but that genomic information is only useful if it’s accurate.”