There’s something in the air: monitoring biodiversity with airborne eDNA

Researchers have discovered that air quality networks collect environmental DNA (eDNA) samples, which can help monitor biodiversity around the world.

Biodiversity has been declining at an alarming rate in recent years, putting ecosystems around the world at risk of collapse. It’s important to quantify biodiversity loss so we can better understand the factors causing it and put measurements in place to limit it; however, we lack the infrastructure required to quantify biodiversity loss at a large scale. Now, an international collaboration of researchers has discovered that the answer may have been under our noses the whole time, in the form of air quality stations, which have been inadvertently collecting eDNA in filters around the world for decades.

“One of the biggest challenges in biodiversity is monitoring at landscape scales – and our data suggest this could be addressed using the already existing networks of air quality monitoring stations, which are regulated by many public and private operators,” commented Elizabeth Clare (York University, Toronto, Canada), senior author of the paper. “These networks have existed for decades, but we have not really considered the ecological value of the samples they collect.”

This work builds on previous studies – one from Clare and her colleagues and one from the University of Copenhagen (Denmark) – that found it was possible to identify species in a zoo by sampling the air. After seeing these papers, co-author James Allerton, who works at the National Physical Laboratory (London, UK), approached Clare with the hypothesis that filters used to collect air quality data might be able to collect airborne eDNA as well.

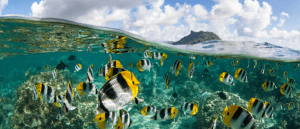

Finding Nemo: using marine eDNA for biomonitoring

Finding Nemo: using marine eDNA for biomonitoring

Using marine eDNA sampling, scientists identified more fish species than with conventional trawling techniques, but only if key implementation steps are followed.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers extracted and amplified eDNA samples from filters at two monitoring stations in the UK. They found the samples contained DNA from over 180 species of plants, fungi, insects, mammals, birds, amphibians and other groups. The list included species of conservation interest, such as hedgehogs and songbirds. In addition, they found that longer sampling times captured an increased number of vertebrate species, probably because more mammals and birds visited the area over time.

The findings of this study suggest that air quality monitoring networks around the world may have been gathering local biodiversity data for many years. As some networks keep samples for decades, the filters could contain data on how biodiversity has changed over time.

“The potential of this cannot be overstated,” first author Joanne Littlefair (Queen Mary University, London, UK) commented. “It could be an absolute gamechanger for tracking and monitoring biodiversity. Almost every country has some kind of air pollution monitoring system or network, either government owned or private, and in many cases both. This could solve a global problem of how to measure biodiversity at a massive scale.”

The next step is for the team to preserve samples with eDNA in mind and encourage others to take advantage of the biodiversity data that the filters contain.