A happy ending for the three blind mice?

A simple injection has been found to restore sight in blind mice, providing vision good enough to distinguish objects and shapes.

A team of researchers from UC Berkeley (CA, USA) led by senior author Ehud Isacoff, has found that injecting a nullified virus containing a gene found in light receptors into the eyes of blind mice can restore sight to a highly functional level.

One in ten people over the age of 55 are affected by macular degeneration; a total of 170 million people world-wide suffer from the condition and a further 1.7 million are affected by the inherited condition retinitis pigmentosa, which characteristically leads to a loss of sight by the age of 40. Treatment options for these patients are currently insufficient to restore functional sight and often simply focus on slowing the degeneration of the retina’s photoreceptor cells, which causes the blindness.

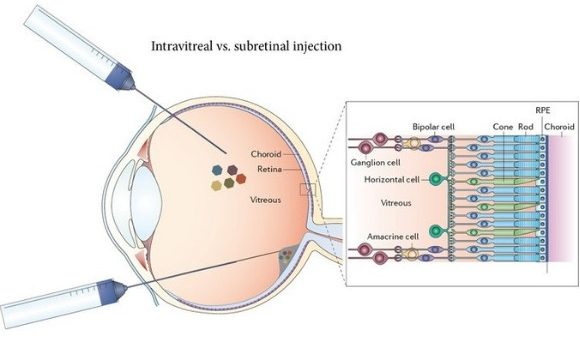

Isacoff and his team focused on the fact that while photoreceptor cells are degraded, bi-polar and retinal ganglion cells are often spared. While these cells are not responsive to light, Isacoff hypothesized that they could be manipulated to become light sensitive.

The research team began by designing a virus to carry a gene to the ganglion cells, selecting an adeno-associated virus that targets ganglions in its wild type. They then selected the genes for delivery to the ganglion cells, Identifying the light receptor genes as vital to the process.

“You would inject this virus into a person’s eye and, a couple months later, they’d be seeing something.”

The team first examined the gene for rhodopsin, the protein found on the surface of rod cells, which is more sensitive to light than the cone opsins. This gene was delivered in the virus via an injection into the retina of mice whose cone and rod cells had completely degenerated. These mice regained the ability to tell light from dark even at low levels of light. However, rhodopsin responded to light signals too slow for the mice to perceive shapes.

The team repeated the experiment with the gene for green cone opsin. The results were phenomenal. The green cone opsin responded to signals ten-times quicker than rhodopsin, allowing the mice to distinguish between parallel and horizontal lines. The treated mice were also found to be capable of navigating obstacles. The change in the quality of vision for the mice was so dramatic that study co-author John Flannery exclaimed, “to the limits that we can test the mice, you can’t tell the optogenetically-treated mice’s behavior from the normal mice without special equipment.”

“This powerfully brought the message home,” Isacoff said. “After all, how wonderful it would be for blind people to regain the ability to read a standard computer monitor, communicate by video, watch a movie.”

Isacoff and Flannery are confident that this treatment could become a viable option for humans in the future. “You would inject this virus into a person’s eye and, a couple months later, they’d be seeing something. With neurodegenerative diseases of the retina, often all people try to do is halt or slow further degeneration. But something that restores an image in a few months — it is an amazing thing to think about,” explained Isacoff.

“When everyone says it will never work and that you’re crazy, it usually means that you are onto something”

Before this can dream can become a reality there are a few hurdles to overcome. In mice it was relatively simple to deliver the virus to the majority of ganglion cells, but in humans this could become more of a mammoth task as the number of ganglion cells in human eyes outnumber those in mice by orders of magnitude.

The team is now working on variations of the procedure to fine-tune it leading to the hopeful restoration of color vision and even better visual acuity. Meanwhile, despite some of the skepticism that the study was met with along the way, they are also working to raise funds, to take this research into the human trial stage in the next 3 years. “When everyone says it will never work and that you’re crazy, it usually means that you are onto something,” remarked Flannery.