Smarty pants

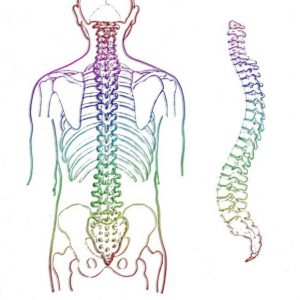

What is the function of the spinal cord? Scientists find that the spinal cord may play a bigger role in movement control and be ‘smarter’ than originally believed.

New research from the University of Western Ontario (ON, Canada) has found that the spinal cord may be ‘smarter’ than originally thought. As well as playing an important role in the pain reflex and aspects of basic motor-control, it may also be able to process more complex functions such as the positioning of limbs in external space.

In a study recently published in Nature Neuroscience, participants were asked to maintain their hand in one position as it was bumped by a specialized robotic technology called the three degree of freedom exoskeleton. The kind of motor control needed requires sensory input from multiple joints to be converted into motor commands.

“Spinal circuits don’t really care about what’s happening at the individual joints, they care about where the hand is in the external world and generate a response that tries to put the hand back to where it came from.”

The time that it took for the muscles in the elbow and wrist to respond to the bump from the robot was measured along with whether these responses helped in bringing the hand back to the initial position. By measuring the time of the response, it was possible to determine whether the processing was occurring in the spinal cord or in the brain.

“We found that these responses happen so quickly that the only place that they could be generated from is the spinal circuits themselves,” commented the study’s lead researcher Jeff Weiler. “What we see is that these spinal circuits don’t really care about what’s happening at the individual joints, they care about where the hand is in the external world and generate a response that tries to put the hand back to where it came from.”

This response is known as the stretch reflex and has previously been thought to have little effect in helping movement.

“Historically it was believed that these spinal reflexes just act to restore the length of the muscle to whatever happened before the stretch occurred,” commented senior author Andrew Pruszynski. “We are showing they can actually do something much more complicated – control the hand in space.”

“This research has shown that a least one important function is being done at the level of the spinal cord and it opens up a whole new area of investigation to say, ‘what else is done at the spinal level and what else have we potentially missed in this domain?’,” he added.

The results add to the current understanding of neurocircuitry and movement and provide new information which may benefit rehabilitation science.

“A fundamental understanding of the neurocircuits is critical for making any kind of progress on rehabilitation front,” explained Pruszynski. “Here we can see how this knowledge could lead to different kinds of training regimens that focus on the spinal circuitry.”