The fly’s the limit! Naturally occurring protein boosts the beneficial effect of exercise in flies

New research demonstrates that the protein Sestrin mimics the benefits of exercise in the muscles of flies and mice.

The benefits of exercise are well established as a vital part of a healthy lifestyle. Regular exercise is effective for minimizing the effects of age-associated mobility impairments, as well as decreasing the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.

Now, a collaborative study led by the University of Michigan (MI, USA) has demonstrated the vital role of Sestrin – a small stress-inducible protein – in mediating the benefits of exercise.

“Researchers have previously observed that Sestrin accumulates in muscle following exercise,” explained the study’s lead author Myungjin Kim (University of Michigan).

To further explore the role of Sestrin in exercise, the team created Drosophila knockouts that lacked Sestrin expression, as well as mutants in which Sestrin was overexpressed.

To monitor the flies’ exercise levels, the team utilized a piece of climbing equipment known as the ‘power tower’, which they had previously developed. It functions as a fly treadmill, exploiting the natural climbing instinct of flies.

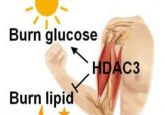

The flies were trained for 3 weeks using the treadmill, the wildtype flies’ ability improved over the cause of the training, whereas the flies that lacked Sestrin did not. This effect was replicated in Sestrin knockout murine models, who did not experience the improved aerobic capacity, respiration or fat burning normally developed through regular exercise.

- You no longer need to feel guilty for a lazy weekend

- Why we “hit the wall”

- Epigenetics and metabolism: what do we know?

“We propose that Sestrin can coordinate these biological activities by turning on or off different metabolic pathways,” commented study author Jun Hee Lee (University of Michigan). “This kind of combined effect is important for producing exercise’s effects.”

Flies in which Sestrin was overexpressed were observed to experience exercise-associated benefits at higher levels than the trained wildtype flies, demonstrating that Sestrin conferred a greater benefit than exercising alone.

In an independent study, Lee, with co-collaborator Pura Muñoz-Cánoves (University Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain), demonstrated that Sestrin can prevent muscle atrophy in immobilized limbs, highlighting the potential applications of Sestrin for replicating the effects of movement and exercise.

While these results are promising, people shouldn’t hang up their trainers just yet. Sestrin supplements are still a long way off, Lee explained: “Sestrins are not small molecules, but we are working to find small molecule modulators of Sestrin.”

Additional research is also needed to understand the mechanism by which exercise induces the production of Sestrin. The potential findings could have implications for combating muscle wastage in the elderly and individuals unable to exercise.