Dolphins use corals and sponges to self-medicate skin conditions

After observing bottlenose dolphins rubbing along corals, researchers believe certain corals and sponges may have medicinal properties and have analyzed samples to find out.

Angela Ziltener is a wildlife biologist at the University of Zurich (Switzerland) and the co-lead author of a study that analyzed coral samples to learn why dolphins queue up to rub along them from nose to tail. Ziltener explains that 13 years ago, she first observed dolphins doing this in the Northern Red Sea near Egypt. “I hadn’t seen this coral rubbing behavior described before, and it was clear that the dolphins knew exactly which coral they wanted to use,” says Ziltener. “I thought: ‘there must be a reason.’”

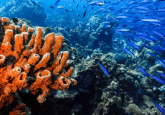

As Ziltener is a diver, she was able to study the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins underwater after earning the trust of a pod of dolphins that, luckily, were not too phased by the large bubbles released by the diving tanks. Once Ziltener was able to visit the pod regularly, the collaborative team from universities across Germany could identify which corals the dolphins were selecting and collect samples to analyze. They found that the dolphins were agitating small polyps that make up the coral communities, which release mucus.

The dolphins would choose specific invertebrates, including gorgonian coral (Rumphella aggregate), leather coral (Sarcophyton sp.), and sponge (Ircinia sp.). The team used high-performance thin-layer chromatography and on-surface assays along with high-resolution mass spectrometry to analyze the collected coral samples. The analysis revealed 17 active metabolites with antibacterial, antioxidative, hormonal, and toxic activities.

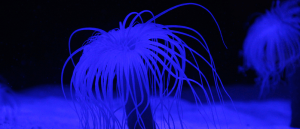

Sea anemones evolved to repurpose neurons as stinging cells

Sea anemones evolved to repurpose neurons as stinging cells

Stinging cells called cnidocytes could be a beneficial model to understand the emergence of new cell types, which has been a challenge in evolutionary biology.

Due to these metabolites, the research team believes that the mucus from the corals and sponges is regulating the microbiome on the dolphin’s skin, as well as treating any infections. “Repeated rubbing allows the active metabolites to come into contact with the skin of the dolphins,” explains Gertrud Morlock (Justus Liebig University of Giessen, Germany), the co-lead author of the paper. “These metabolites could help them achieve skin homeostasis and be useful for prophylaxis or auxiliary treatment against microbial infections.”

The reefs where these corals are found are where local dolphin populations head for a bit of rest and relaxation. “Many people don’t realize that these coral reefs are bedrooms for the dolphins, and playgrounds as well,” explains Ziltener. After a restful nap, the dolphins are often found rubbing against the coral. “It’s almost like they are showering, cleaning themselves before they go to sleep or get up for the day.”

Ziltener began her research on dolphins in Egypt in 2009 and has noticed that dolphin swimming has become increasingly popular, which is disturbing dolphins in their hang-out spots. So, Ziltener started a conservation group called Dolphin Watch Alliance to educate tour guides, tourists and the public on making sure that these tourist experiences are safe for dolphins.

This group is also lobbying for the reefs to become protected, which is not only essential for the dolphins but also means that researchers can continue to study this coral rubbing behavior. Further research is needed to confirm and determine the medicinal properties of different corals, and how the dolphins use these on different parts of their body.