Pet dogs to the rescue

A recent study investigating the intent behind a dog’s desire to rescue shows that pet dogs are likely motivated by more than obedience to save their owners.

As the world entered lockdown thanks to COVID-19, animal shelters across the globe found themselves facing a surge in interest. The UK’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals reported an increase of 600% in visits to its dog fostering pages and breeders reported that the UK may be facing a puppy shortage as waiting lists for dogs increased fourfold. For those self-isolating alone, pet dogs can provide the companionship and comfort lost due to social distancing measures.

The bond between humans and such canine companions has always been strong – they are not called man’s best friend for nothing – and it is no surprise that many have turned their way during such difficult times. Movies like Lassie or Bolt, as well as real-life stories such as Greyfriars Bobby, depict dogs’ strong love for their owner and penchant for a daring rescue, yet there is little understanding behind a dog’s intent: do they really want to rescue you?

Now, researchers at Arizona State University (AZ, USA) have investigated a dogs’ desire to rescue by setting up an experiment that tested the owner-rescuing capabilities of 60 pet dogs, none of whom had had any prior training.

As part of the rescue scenario, each dogs’ owner sat inside a box with a light-weight door that the dog was able to move aside. From inside the box, the owner would then feign distress by calling out for help. The owners were each coached on sounding authentic in their distress and were told to avoid calling the dog’s name as this would encourage the dog to act out of obedience rather than concern for the owner.

In a subsequent control test, the dogs watched a researcher drop food into the box and it was then recorded whether they opened the box for food or not.

They found that about one-third of the dogs successfully opened the box and rescued their owner. In comparison, 19 of the 60 opened the box for the food. Being as likely to open the box for food as to rescue their seemingly distressed owner suggests that reuniting with their owner could be a highly rewarding action for the dogs.

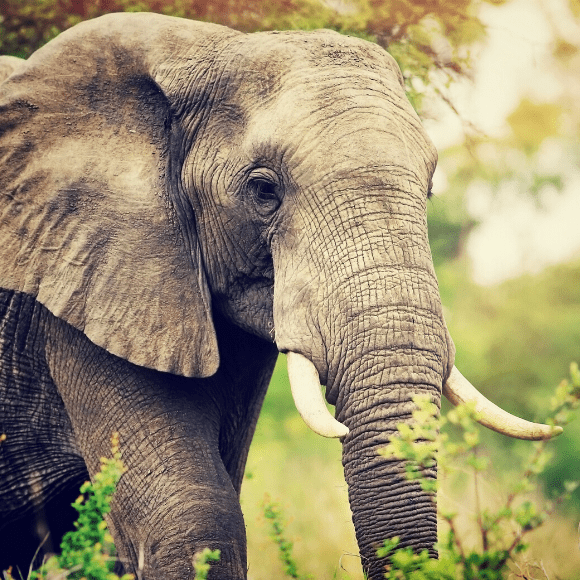

Inebriated animals: can elephants get tipsy?

Inebriated animals: can elephants get tipsy?

A new study finds that, due to a genetic dysfunction, elephants could have a particularly low alcohol tolerance, meaning (theoretically) they could get drunk.

It is important to note that there are multiple factors at play in this experiment, and only one-third of dogs completing the ‘rescue’ is more impressive than it initially seems. The food control provides a clear motivator for the dogs to open the door and showed that the main limiting factor to the dogs opening the door was their ability to do so, as opposed to motivation.

“The key here is that without controlling for each dog’s understanding of how to open the box, the proportion of dogs who rescued their owners greatly underestimates the proportion of dogs who wanted to rescue their owners,” commented Joshua Van Bourg, the study’s first author.

“The fact that two-thirds of the dogs didn’t even open the box for food is a pretty strong indication that rescuing requires more than just motivation, there’s something else involved, and that’s the ability component. If you look at only those 19 dogs that showed us they were able to open the door in the food test, 84% of them rescued their owners. So, most dogs want to rescue you, but they need to know how,” Van Bourg added.

For a second control test, the owners sat inside the box once again, this time reading calmly aloud from a magazine rather than shouting in distress. In this scenario, 16 of the dogs still opened the box, suggesting it is not always about rescuing – sometimes dogs just want to be with their owners. However, as more opened the box during the distress test this indicates that rescuing is not solely about a desire for proximity.

As well as recording whether or not the dogs opened the box, the research team also observed the animal’s behavior during each test, noting that the dogs were much more stressed during the distress test. This stress did not diminish upon repeated exposure to the situation, as it did during the two control tests where they became acclimated to the situation. Such behavior suggests evidence of “emotional contagion” – or empathy – whereby the owner’s stress is felt by the dog.

“What’s fascinating about this study is that it shows that dogs really care about their people,” commented study author Clive Wynne. “Even without training, many dogs will try and rescue people who appear to be in distress — and when they fail, we can still see how upset they are. The results from the control tests indicate that dogs who fail to rescue their people are unable to understand what to do – it’s not that they don’t care about their people.”